✘ Mood Machines, superfans, and music culture that sucks

And: The music-tech ownership ouroboros; The ghosts in the machine; The ugly truth about Spotify

“The culture of the music world sucks.”

In 2018, I saw Nine Inch Nails play at Brooklyn’s legendary King’s Theater. That was a bucket list show for me – I’d long shrouded myself in the darkness of the Nine. And their influence persists. The Fragile and The Downward Spiral both remain on steady rotation, the latter a frequent reference for my own forthcoming EP.

This weekend, Reznor and NIN running mate Atticus Ross won the Best Score Golden Globe for their work on Challengers. It’s their third such award, following scores for The Social Network and Soul – and the latest accolade in a history chock full of them.

Across their career, Nine Inch Nails have sold 20 million records and earned 13 Grammy nominations. Rolling Stone included the band amongst its 100 greatest artists of all time. Suffice to say the music industry has not been unkind to the Nine.

But that hasn’t blinded Reznor from its shortcomings. Here are his words in a recent interview with Indiewire:

“What we’re looking for [from film] is the collaborative experience with interesting people. We haven’t gotten that from the music world necessarily… You mentioned disillusionment with the music world? Yes. The culture of the music world sucks.

That’s another conversation, but what technology has done to disrupt the music business in terms of not only how people listen to music but the value they place on it is defeating. I’m not saying that as an old man yelling at clouds, but as a music lover who grew up where music was the main thing. Music [now] feels largely relegated to something that happens in the background or while you’re doing something else. That’s a long, bitter story.”

As a reader of the Beat and MUSIC x (this edition is getting published in both), I imagine you’re a music lover where music continues to be “the main thing.” You likely share Reznor’s frustrations and have your own long, bitter story.

Perhaps you’re actively engaged in building technology that vaults music back into the fore. Maybe you’re simply a superfan along for the ride. Whatever the case, we can relish in the fact that none of us want the culture of the music world to suck.

But how do we give that long, bitter story a happy ending…

Superfans

It’s no secret that superfans have been a focal point of builders these past couple years. They’re a would-be salve for the one-size fits all, music-as-wallpaper streaming paradigm that we generally agree sucks.

The promise behind superfans is hardly new. Countless startups have attempted to nail “fan engagement” – to manifest the logic behind Kevin Kelly’s 1,000 true fans and Li Jin’s 100 true fans theories. All creators need to do is find their diehards and they’ll be set!

The issue, of course, is finding them – and doing it in a way that elides insidious platform mechanics. To do so, one must understand how and where to source, parse and process platform data.

_____

About a year ago, I covered Water & Music’s sweeping eight-part Music Marketing Data Bootcamp, testing many of its lessons in my ongoing Pariah Carey series. I set targets, assessed various data tools, created a marketing plan, built a CRM (customer relationship manager), probed automation and discovery tools and learned about “gaming the algorithm.”

Pariah Carey is so named for the wordplay, of course, but also because, while musicians you’ve never heard of aren’t pariahs, they may as well be. Algorithms and platforms treat them as such. Don’t want to play the game? Then don’t expect to get any attention – or earn any streaming revenue.

“It still matters that music streaming platforms are driven by profit,” said Bootcamp speaker David Hesmondhalgh, a Professor of Media, Music and Culture at the University of Leeds, “and may therefore have an incentive to keep pushing the work of the most popular artists – or at least not to take active measures to counter that tendency.”

The existence of the ‘game’ – where only the game creators know all the rules and they can change them when they no longer work in their favor – demonstrates the imperative and the challenge of identifying superfans. And with artists growing evermore tired of the game, a budding crop of superfan platforms are emerging to meet their demand.

_____

Just before the holiday, Water & Music hosted a monthly webinar called, “The superfan fallacy: Three hard truths.”

“The music industry's obsession with superfans has reached a fever pitch,” reads the event’s teaser. “While everyone rushes to build the next fan platform or monetization strategy, we're overdue for an honest conversation about what's actually working – and what isn't.”

The three aforementioned hard truths are: “the celebrity superfan complex,” “the reality of data control” and “the platform paradox.”

I want to focus on the last one. In this segment, Hanna Kahlert, an Analyst at MIDIA Research, drew from “years of research on failed attempts and shifting artist and fan behaviors” to argue that “launching new fan platforms isn't the answer to critical fan engagement challenges.”

To unpack that rationale, I’d like to tap our old friend, the journalist and culture theorist Cory Doctorow, who coined the neologism enshittification. The word first appeared in his 2022 blog post, “Social Quitting,” and he expanded upon the idea in a subsequent 2023 post – which was later published in Wired – called “The ‘Enshittification’ of TikTok.”

“Here is how platforms die,” Doctorow wrote, introducing enshittification’s natural lifecycle. “First, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.”

Spotify – whose teased Superfan clubs are about as likely as CEO Daniel Ek understanding music culture – certainly falls within that scope. During the Bootcamp, it was staggering to me that so much energy is expended on “gaming” Spotify – to build tools that parse Spotify data, or fill in gaps for data it doesn’t, or optimize release timing, or predict the likelihood of a playlist feature; or, from an artist’s perspective, literally redesigning your creative practice to accommodate the algo and snag a spot on some mood-based playlist.

Plenty out there are ready for Spotify to arrive at the final point of Doctorow’s enshittification lifecycle (death), and thanks to Liz Pelly’s new book, the platform’s getting a whole new contingent of executioners …

The Beat is Decential’s weekly exploration of music, culture and the new Internet.

On the culture-tech byway, things move at breakneck speeds. From web3 to AI, copyright to collective ownership, art to psychedelics, The Beat is an exercise in association. We all contain multitudes, and within them, vast differences. But there is some connective, fundamental essence to be found.

The Beat is dedicated to that essence, and to the people who seek it; the rest, as Alex Ross wrote, is noise.

LINKS

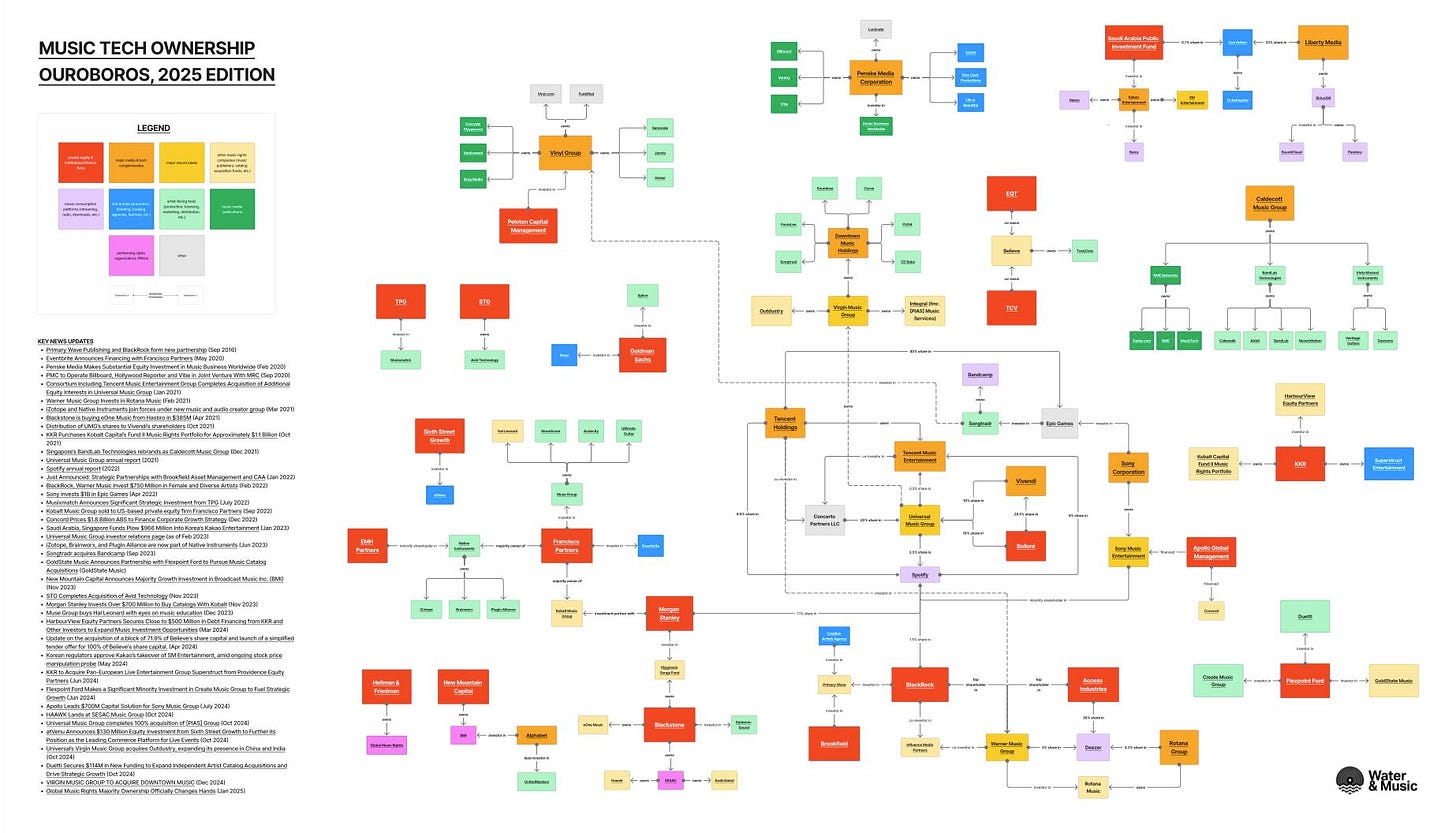

The music-tech ownership ouroboros (Cherie Hu)

✘ Water & Music's latest ownership map just dropped, depicting “the globalization and financialization of power in music and tech.”

It's a good visual overview of our "enshittified" reality, outlining ownership stakes between media conglomerates, sovereign wealth funds, and private equity firms that ensure “the culture of the music world [continues to] suck.”

The ghosts in the machine (Liz Pelly)

“It also raises worrying questions for all of us who listen to music. It puts forth an image of a future in which – as streaming services push music further into the background, and normalize anonymous, low-cost playlist filler – the relationship between listener and artist might be severed completely.”

✘ Harrowing words about what's at stake from an excerpt in Liz Pelly's new book: Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist. The whole piece is damning -- and well worth a read.

The ugly truth about Spotify is finally revealed (Ted Gioia)

“Nobody in the history of music has made more money than the CEO of Spotify. Taylor Swift doesn’t earn that much. Even after fifty years of concertizing, Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger can’t match this kind of wealth.”

✘ And let’s not forget that, in 2021, while 98.6 percent of Spotify artists were earning $36 per quarter, Ek bid $2 billion on a Premier League Football team... Gioia gives us a stark reminder of the exploitative mechanics that Spotify has helped institutionalize.

MUSIC

For my music selection, it was tempting to go with NIN -- I listened to The Fragile on repeat while I wrote this piece -- but for the purposes of amplifying an artist who's had to reckon with the streaming era, I'll choose Mario Batkovic.

I first heard the accordionist in 2017, when his self-titled record was pitched to me for a feature. Then, I listened to the single "Quartere" about a dozen times. It was hypnotic -- minimalism at its finest, toeing that fine line between repetition and change.

But then I forgot about it, until a couple months ago when that song came roaring back to mind. Since then I've devoured his entire catalog, which features collaborations with luminaries like Colin Stetson and James Holden. Still, "Quartere" remains my favorite, and it's excellent starting point for someone looking to dive in.

Well what a delicious feast of perspective and information you served up. I am tired of kissing the ring (Spotify) and who dropped one of my recent singles because of suspicious activity. I am grateful to those who shed light in the darkness on how to deal with all this enshittification.

Honestly, the most important addiction to Spotify that needs to be broken is that of the venue bookers, bloggers, and label reps that judge music artists by Spotify numbers + Instagram followers or TikTok followers. If it weren't for that addiction, Spotty + the others wouldn't be the focus of such intense "gaming" behaviors from artists seeking an edge on their competition.