✘ How to deal with YouTube

And: Licensing AI music; Developing taste; Just for a second; OpenAI will know more about you; UK venues in more trouble

Video is everywhere and YouTube is the big beast that everyone has to contend with. Even though every social media app has their own little or large corner of the Internet that they dominate, it’s YouTube that still seems to run the roost. If you want to work with video online you can definitely choose to avoid YouTube and be successful, but if you feel like you can’t get around it here’s how you can look to tackle a strategy for it.

YouTube at 20

This application has been in our lives for twenty years now. It kickstarted a user-generated content glut and has been a VC-style playbook ever since it started. Big changes in a particular field - in YouTube’s case this is media - come from outside of that field. Interestingly, YouTube is also a case study for selling out too early. Sequoia, one of the leading VC investors into YouTube went through a whole identity shift from its learning around this. As Sebastian Mallaby has described: “[people] are irrationally risk averse when it comes to reaching for upside.” Google has definitely reaped the upsides. YouTube has grown into a platform that has, on average, over 20 million videos uploaded, over 100 million comments on videos, and over 3.5 billion likes on videos - every single day. There’s no denying the influence YouTube has on the daily lives of a lot of people worldwide. And music plays a massive role in this.

Music videos to Shorts

Yes, it started with UGC, but YouTube also called in the revival of the music video. There’s been some pretty stellar hits - from Despacito to This is America. The major labels got involved through Vevo, building out an enormous multi-channel network. This was the early years of YouTube - Vevo started in 2009 - and there was no difference between long-form and short-form content. It was all treated the same. This changed, of course, with TikTok when YouTube felt its rival was taking away too much screentime. It launched Shorts in response, and this has given a whole new life to what video can do on YouTube.

There’s the standard videos we see on a person’s or company’s channel. These videos are monetized through ads and have a preroll, midroll, or postroll ad block. Such videos still vary a lot in length, but the ideal length has been around 8 to 12 minutes for a while now. This is mostly predicated, however, on the types of videos creators make - meaning these are the kind of videos with a host talking to the viewers. Here, consistency in uploading is paramount. The playbook is old-school TV here: make sure people know they should tune in every Thursday at 8pm, as an example.

Shorts are different. These used to be limited to a minute but can already be three minutes nowadays. Shown in a rolling feed - like any other app offers as well - these need to catch your attention immediately. Whereas the longer-form videos on YouTube offer a creator a little moment to build tension, there’s no such thing with Shorts. They need to show what’s going on immediately, or people will have scrolled through. The most important metric for Shorts? If people watch it more than 100%. That means they watched the video through to the end and it started again. Similarly to long-form, you need to consistently upload videos to Shorts. However, this isn’t about timing, but about quantity. Throw 25 videos on there, 22 will do very little, 2 will do well, and 1 one will be your big viral moment. You could try to understand why, but the most important thing is to just keep feeding the machine.

The TV opportunity

A few years ago I wrote about the opportunity afforded to music to tap into the newly established FAST (free ad-supported streaming television) ad revenues. This was about connected TVs bringing through an array of free linear TV channels that offered anything from silly dad jokes to kids TV and endless reruns of old, popular shows. While music is popular, even the most laidback channel can’t beat those three pillars. What we’re seeing with YouTube, however, is that people are watching on their TVs more and more.

This is, of course, US-based data. Across the world, mobile has a 70% usage rate. Considering that the US is the second biggest country in terms of numbers of users, that means that in India - the largest user base by a longshot - most people use mobile. The TV opportunity is definitely connected to those countries with a strong penchant for connected TV viewing anyway.

All this to say that it’s worthwhile thinking about and addressing where an audience might watch the most. TV makes for longer viewing time over mobile. To take a popular example, NPR’s Tiny Desk series won’t work so well as a Short - it’s a short show, but the format includes several songs. Here, it might be interesting to consider whether Shorts can be a funnel to the longer-form channel. My own learning through Symphony.live here is that Shorts are a thing that lives on its own. Shorts lead to channel subscribers but not long-form video views. To take advantage of the TV opportunity, your best best is to create videos that work in the long-form algorithm: basically, creator-driven or music videos. The latter already demand popularity to be successful.

The revenue conundrum

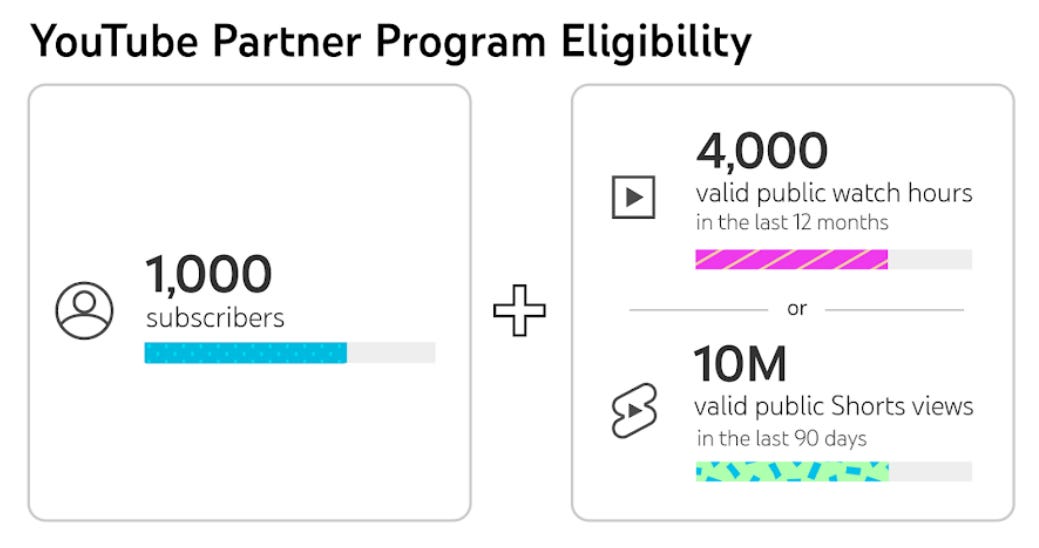

It’s unclear whether there’s different monetization levels between mobile and TV. What is clear, is that you need a certain level of reach and engagement before you can monetize.

Once reached, monetization on Shorts works through a revenue pool divided on watch-time and engagement. On the long-form side of YouTube, revenue is based on a CPM (cost per 1000 impressions) for advertisers and RPM (revenue per 1000 views). These two won’t match, because YouTube has to shave off a bunch of costs, etc. One of these - and the same goes for Shorts - is music licensing. On the Shorts side, YouTube takes 20% for music licensing across the board, whether a video uses music or not. On the long-form side, licenses are paid directly when music has been used. What’s more, a copyright owner can claim the ad revenue on your video if they have proven their ownership.

So, what to do here? Revenue on YouTube is really only interesting if you have a lot of reach and retain full ownership of the content you create. Any strategy that involves monetization should first focus on building that audience. Monetization follows strategy here.

Going where your audience is

So many people use YouTube as a daily habit, countries like Spain, the Netherlands, and Australia have close to 90% penetration, meaning they’ve installed the app or navigate to the website. This kind of reach and engagement means that creators - in the broadest sense of the term - move towards it. This happens across a broad spectrum. YouTube isn’t just native content creators and influencers. It’s also public broadcasters who see putting their content on there as a necessary route to reaching their audiences. These people spend less time in front of their traditional TV channels. Instead they are on their phones or using apps on the connected TV.

Take the UK’s Channel 4, they devised an entire slate of original programming for their YouTube channel dubbed Channel 4.0. This strategy is successful, they have over 750k subs and recently a format that started on YouTube has been picked up by an international distribution agency. These are all legacy brands that often adopted YouTube early on often giving them early-mover advantages. What’s more, they devised specific strategies for the medium. They see it not as a funnel, but as a place where an audience they should be catering for actually spends time. They then create the kind of content that resonates with these audiences and bring it to them where they are.

Do

Think about what you create.

Think about your audience on YouTube - or any other platform for that matter.

Cater to this audience with your video content.

Check what works for you.

Don’t

Try to understand the algorithm.

Think you can move one audience to another platform - YouTube or otherwise.

Repeat content strategies across platforms.

Be afraid to fail.

LINKS

🔣 Licensing AI music: the industry is focusing on the wrong problem (Virginie Berger)

“This means that every output is a reflection of everything the model has been trained on, not a direct copy of one input, but a statistical remix of all prior ingestion. Licensing one song here and there after the model is built misses the point entirely. The damage happens during training, not when an output is published.”

✘ Unlike many other people shouting we need to change the way we approach copyright and protection in the case of large models and GenAI, Virginie actually considers solutions. She’s also able to put her finger on the nerve of the actual problem - input, not output.

🧂 Developing taste (Emily Kowalski)

“But what is good taste? It’s commonly mistaken as personal preference, but it’s more than that — it’s a trained instinct. The ability to see beyond the obvious and recognize what elevates. It’s why some designs feel effortless. So the real question is, how do you train that instinct?”

✘ This goes to the heart of a problem we’ve faced for a while now and which rises to the surface again as AI makes everything more ‘efficient.’ What sets good apart from bad comes from the moment of inspiration that leads to creating.

🫵 Just for a second I thought I remembered you (Rob Horning)

“Now chatbots are being put to work on the same ideological project: Here are entertainment products that you can treat as friends, just as you have become accustomed to regarding your friends as entertainment products.”

✘ Remember that famous adage: the medium is the message? It’s still an ongoing process where each new technology of mediation reinforces how we relate to other humans and non-humans alike.

🕵️ Meta knows a lot about you. OpenAI will know more. If it doesn't already... (Bas Grasmayer)

“Still, the data Zuckerberg has been collecting pales in comparison with what people entrust ChatGPT with. That ranges from work-related data, all kinds of stuff people would normally Google, the expression of people’s most outlandish fantasies through image creation, help with personal emails and messages, and secrets from the depths of their psyche that they may not even share with their closest friends. All in one place.”

✘ Everything you put into a chatbot becomes training data. Full stop. If you’re not aware of this yet, you are now. Bas gives some great advice on how to move around this situation in this post.

🏛️ UK falling far behind in battle for venues and artists: “Music becomes a middle and upper class sport” (Andrew Trendell)

“[Mark] Davyd [of Music Venue Trust] further explained that venues were facing “a very tough year” and that recommendations beyond the levy were being ignored by the government – including “very damaging” business rates, taxes increasing on venues by £7million, and no action on VAT with the UK experiencing the highest rates anywhere in the world on new and emerging music.”

✘ Considering my post last week, this is very disconcerting. The call to action here is simple and not hard to implement: 1 Pound on every ticket sold to major gigs around the UK to establish a fund to help smaller, grassroots, venues.

MUSIC

The new record by Klara-Lis Cloverdale is a beautiful exploration of what can broadly be called ambient music. It’s music that sits in a long history of computer-music composition, modular developments and engagement of electronics with instruments. There is, for example, some beautiful cello work in there as well as software manipulation. For me, it shows Cloverdale coming into her own as a composer.