✘ Fortnite, Minecraft and Meta Too: is the future of touring virtual?

And: Curtis Institute of Music launches music label; Protein's new report on ownership; A thesis for building enduring Web3 communities

In 2019, Charlie Brooker’s dystopian anthology television series ‘Black Mirror’ released “Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too”. The episode follows Ashley O, a fictional wig-wearing pop singer whose creative agency is stifled by her image-obsessed management (much deliberately played by Miley Cyrus of Hannah Montana fame). Upon rebelling against her pop obligations, Ashley O is rendered unconscious by her management. This proves to be an exploitable business opportunity, as, thanks to state-of-the-art technology, they are able to keep their money-maker not only releasing music but also touring. As the episode climaxes, Ashley O’s management unveils a holographic touring replacement for the singer, dubbed “Ashley Eternal”. Unbeknownst to them, the real Ashley has been rescued by super-fan Rachel and her sister, the episode’s protagonists. It finishes with Ashley performing Nine Inch Nails in an ill-lit rock bar - a stark contrast to the bubblegum version of “Head Like A Hole” (then swapped for the consumer-friendly ‘On A Roll’) she had been previously performing as an automatonlike commodified pop idol - with or without her consent.

“Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too” is not good. In fact, it is arguably the worst “Black Mirror” episode ever, with a score of 6.1 on IMDB - the lowest of the series thus far. But, despite the ham-fisted message and the sloppy writing, it still serves as evidence that there was something to be said about virtual touring - and its potential ethical pitfalls - much before the moment it is having now. Brooker claimed to have been inspired by the real-life holographic performances of dead artists such as Prince and Whitney Houston, the likes of which he deemed “ghoulish”.

The prickly moral nature of virtually resuscitating the deceased for profit and entertainment is undoubtedly perfect “Black Mirror” fodder. But, even though the reality is not quite as cartoonishly devilish, virtual performances have become a legitimate avenue for musicians who have become disenchanted with playing live “the old way”. The touring industry is currently undergoing a severe crisis for reasons we have outlined here, here, and here. Could it be in need of a virtual upheaval?

ABBA may think so. This May, the Swedish pop juggernauts “embarked” on a virtual concert residency in a purpose-built venue at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London featuring virtual avatars (or ABBAtars…) depicting the band as they were in 1977. It has proven successful; as NME’S Andrew Trendell jokingly put it in his five-star review of the show, “we for one welcome our new ABBAtar overlords”.

Before, during, and after the pandemic, other high-profile acts have followed suit - Marshmello, Travis Scott, and Ariana Grande, for instance, have all held highly successful performances in Epic Games’ online video game Fortnite. And many more have ventured into virtual reality performances since - so many, in fact, that this year the MTV Video Music Awards introduced a brand new category, “Best Metaverse Performance”, bolstering virtual live music’s future prospects as part of what is to come for the touring sector. As each new experience proves to be more successful than the one before, they seem less like a fad, and more like a rehearsal for the future of touring. Given the live music industry is in shambles, a virtual future may not be such a bad idea. But what is attracting musicians to virtual performances? Will they ditch the road and go online? Will we follow?

Watching them made me euphoric and a little weepy

As with Hemingway’s description of bankruptcy, virtual concert experiences happened “gradually, then suddenly”. The scene, best leveraged during the pandemic, had been previously set by other trials; and, during the lockdown, it expanded into what it has grown to become today and for the foreseeable future.

As the world was forced online, the perfect opportunity came for virtual concert activities to rise to the occasion. That is why 2020 saw some of the most successful instances of mainstream virtual live music thus far, such as the case of Travis Scott’s Fortnite venture in April 2020.

Problematic as it may be to say following the Astroworld festival disaster, the Houston rapper’s larger-than-life shows were then highly sought-after. Under the spring lockdown, 28 million of his fans gathered (virtually) to see him play in no other arena than Epic Games’ Fortnite. Scott made the most of the virtual game’s boundless nature, starting his 10-minute set by emerging from an exploding asteroid and leading gamers underwater and into space. He also premiered ‘The Scotts’, his Kid Cudi collaboration. The concert reportedly generated $20 million for Scott.

The game had held its first virtual concert more than a year prior; in early 2019, masked EDM DJ Marshmello played to a virtual audience of 10 million, leveraging a soon-after dropped Fortnite merchandise line and a broad array of new young fans. At the time, “real” live music was alive and kicking, and the concert discovery service SongKick saw a 3,000% increase in searches for Marshmello. His socials exploded - he gained 62,000 new followers on Twitter, and 260,000 on Instagram. According to Billboard, his YouTube following grew too - by 1,800%. By then, the industry had no choice but to start taking virtual concert performances’ real-life potential seriously.

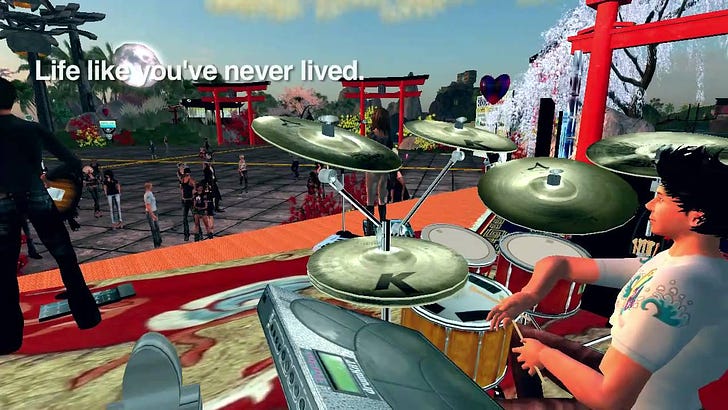

Fortnite did not, however, invent the concept of live music in virtual spaces. As early as 2007, the model of virtual live music was being tested by what Rolling Stone then deemed “the future of the net”; the trailblazing online multimedia platform Second Life. There, musicians chanced virtual performances to varying degrees of success. At the time, disillusioned The Guardian reporter Guy Dammann observed Second Life proved to be a rather hostile environment for a concert. But, he noted, that was not the point;

“an event is marked more by its fostering of a kind of virtual being-together than by the actual quality of what is currently on offer”.

Nevertheless, throughout the years, gaming companies have insisted on bettering the format and setting a new precedent for virtual performances. This is one that allows for new creative possibilities in set design, world-building, and revenue streams for artists without foregoing what makes the experience special and unique - the music.

Much before Epic Games and others like it, forward-thinking acts like Radiohead and Björk were pioneering the relationship between virtual reality, technology, and music. And, since then, the model has been refined many times - to the point that Dammann may be eating his words today. In the thick of the pandemic, Pitchfork’s Cat Zhang expressed the emotional experience of attending a festival again, even if virtually. About experimental pop duo 100 Gecs’ Square Garden Music Festival on Minecraft (a virtual gathering attended by Charli XCX, Kero Kero Bonito, and more), she wrote:

“watching them made me euphoric and a little weepy—it’s been so long since I’ve seen a crowd”.

Sure, we were in May 2020, and our relationship with concerts was warped by the ongoing lockdown; but, when compared to Dammann’s withered impression of what virtual live music could offer in 2007, it is clear that thirteen years later something changed. But now that live music is back (even if shakily), it is worth revisiting the question of whether that emotional response can be duplicated behind a screen. Or is the experience of sweating in the concert pit simply irreplaceable? And, even if it is not, can the tech sector, currently (also) in crisis, fill the market gap?

Is it fair to be cynical about this new utopia?

Now that lockdown has come and gone, it is clear culture has continued steadily moving virtually. When it comes to live music, experiences such as the ones made by Scott, 100 Gecs, and many, many more, prove there is room for live music to roam in virtual settings. Maybe, the audience’s appetite for virtual experiences is not only because of our collective shift into ever-online but also to live music’s less-than-stellar post-pandemic return. However, the change has not occurred without criticism, with many, not unlike Brooker, poking holes in a virtual future.

Despite the shaky course its biggest proponent currently undergoing, the metaverse has been continuously buzzing for the last few years. Paired with the rise of NFTs and a growing crossover between music and online gaming, it is only natural for us to start musing on what role music will play in the virtual world - and what issues may arise.

Many have begun by pointing out the potential accessibility and diversity challenges. Namely, even as the metaverse offers endless creative, cultural, and economic possibilities for musicians, which ones will get to leverage them? For now, the paradigm has been most splashily capitalized on by A-listers like Scott and Grande - and, even when straying away from the mainstream, 100 Gecs are still a band with tremendous (even if niche) cultural capital. Although the metaverse could be a treasure trove for many independent musicians, offering a new place to foster community and seek revenue streams (via the selling of music and merchandise as NFTs, for example), according to Rolling Stones’ Paul Herrera, “a metaverse takeover by artists outside the major-label system still seems out of reach”. Collaborating with titans such as Fortnite and Minecraft entails costs many are not able to support, as these virtual performances involve paying software developers, 3D modelers, tool builders, and many other human resources. There are companies like Blender which could make independent artists’ foray into the metaverse easier, as they provide open-source asset creation tools for all; however, there is not yet a formal platform allowing artists to create a playable metaverse experience for fans. And, while that road is not yet paved, not all will be let in the world of possibilities offered by virtual landscapes.

Inder Phull is the co-founder and CEO of PIXELYNX, a company building technology and acquiring equity in a range of startups that, they say, “will form the foundation of how music is experienced in the metaverse”. For him, it is natural musicians moving towards virtual reality are worried about swimming against the current of the all-encompassing algorithm, too. Rolling Stones’ Declan McGlynn asks;

“Given that it’s Facebook – now Meta – leading the charge for widespread metaverse adoption, is it fair to be cynical about this new utopia not offering the direct-to-fan experience some are championing?”

For Phull, there is no clear answer, as he says that the power struggle between curators and algorithms, a staple of current-day social media, is likely going nowhere fast. There is the possibility, however, of smaller musicians being able to make use of smaller, niche platforms, in which finding community won’t be as hard as on the big fish tanks of Fortnite or Minecraft, where they would have to go up against mainstream sharks. These tight-knit spaces could be smaller musicians’ way of avoiding turning themselves into an Ashley O-like figure, having to endlessly repackage themselves in order to thrive under tech capitalism.

Even if we eventually get over accessibility and algorithm issues when it comes to virtual live music, is there still an ethical itch in moving a tour to the metaverse, as the one Brooker attempted to scratch on his 2019 Black Mirror episode? While musing on the moral pitfalls of turning our lives meta certainly is interesting, it may need to wait until we know just what we are philosophizing about. This is because, as we publish this final piece to our touring crisis series, the tech industry is also going through a “mid-life crisis”, as The Atlantic said last week. As layoffs in just about every major company, (yes, even Meta) pile up week-to-week and stock valuations for many of them continue to plummet, the sensation is that tech has come to a standstill - much like touring. Post-pandemic, the world is bound to change, in ways that we are still grasping to figure out. Wishful thinkers say we are turning the page, moving ahead; cynics say this is the beginning of the end. As for touring musicians, only time will tell if there is a better home for them in the virtual future, and what that may look like. But, for now, we do not need to stick to mid-tier Black Mirror episodes to imagine it - virtual live music is happening as we speak. So far, we hope, so good; in the future, let us try to make it better than what we have right now.

LINKS

🎙️ Curtis Institute of Music launches new record label (Hattie Butterworth)

“Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music has today announced the launch of its own label, Curtis Studio. Focusing on the discovery of both new and traditional works performed by inspiring artists of our time, the label will give Curtis students the opportunity to learn about the process of making a recording.”

🧼 Dirty Words #3: Ownership (Protein)

“61% of our survey respondents want loyal consumers to have more say in how brands operate, and some believe businesses should move towards collective and worker ownership. This is particularly felt by Gen Z (34%) and Millennials (40%). It’s clear that business structure can impact overall brand perception.”

Download the full report here

👐 A Culture of Intimacy: a thesis for building enduring web3 communities (Steph Alinsug & Rafa the Builder)

“In DAOs, we take the concept of product-market-fit and recast it as community-market-fit. Community — the DAO — is the product. A worthwhile starting place for community-market-fit is the creation of intimacy between genesis members. This intimacy is expressed as strong inter-member empathy and the elusive condition of trust.”

MUSIC

I would be remiss to finish this series without referencing my favorite record of all time. Have you ever heard a piece of music so often that you are afraid to metaphorically break it? I have been wearing Joanna Newsom's 2006 magnum opus "Ys" on my sleeve so hard since I first encountered it that it is now more of a worn-out sonic comfort blanket than a simple record to me. If this makes at least one person revisit it - or, better yet, discover it -, my work here is done.

[self promo alert]

I'd be remiss to not mention a project I worked on with Vienna based Tin Man over the pandemic https://www.raveblocks.com/ ... we built a virtual Berlin and hosted some DJ sets.. we even built a record shop where you could listen to and buy (clicks out to bandcamp) the music.

https://www.youtube.com/@raveblocks2629/videos